Radio as a form of struggle: scenes from late colonial Angola

The Conversation

02 Dec 2019, 20:07 GMT+10

One August night in 1967 in the village of Mungo in central Angola, the local colonial administrator walked into a bar to buy cigarettes. As he entered, he noticed furtive gestures. The barman, Timoteo Chingualulo, turned down the volume on the radio and Chigualulo's friend, Antonio Francisco da Silva "Baiao," a nurse at the health delegation, changed the station.

After the administrator left, they returned to the original programming: Radio Brazzaville broadcasting the show Angola Combatente (Fighting Angola). The administrator could hear the show from his veranda. He reported this to the police, who arrested the two men - and took the offending radio.

The police found no evidence that the men were members of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola), the liberation movement fighting for independence from Portugal. The movement was responsible for creating Angola Combatente, which was broadcast from Brazzaville in the neighbouring Republic of the Congo.

But, as the police document recounts:

I heard and read stories like this over and over in interviews and archival research I did on radio and the state in Angola for my new book Powerful Frequencies: Radio, State Power, and the Cold War in Angola, 1931-2002. During research for my previous book Intonations, musicians and others remembered listening in hiding and using the colonial state broadcaster to promote their music.

In Powerful Frequencies, I argue that the colonial state and independent state used radio to project their power. But, like the story of Chingualulo and da Silva, listeners had their own ways of getting and disseminating information and news. Radio broadcasting and listening is not just about content, though. How radio works is as important as what radio says. Technology matters to, but doesn't determine, how people produce meaning. The history of radio and state in Angola should remind us that the problems of fake news, bots, and infiltrated media ecosystems that make the headlines today have antecedents. They are also human problems that require human solutions.

An anti-colonial war raged in Angola from 1961 until 1974. This shaped life in the Portuguese territory, including the habits of how Angolans listened to radio.

Many sought out news and information from a variety of sources. The colonial administration censored the local press and radio, controlling for news about the war and the national liberation movements that fought it. People - whether African labourers or black civil servants or white settlers - tuned into national and international broadcasters. The BBC, Radio France Internationale, the Voice of America, and Radio Moscow all broadcast in Portuguese.

The Portuguese secret police) followed these broadcasts, often transcribing them word for word, calling them "anti-Portuguese broadcasts".

Angola Combatente or Voz Livre de Angola (the National Front for the Liberation of Angola's programme broadcast from Kinshasa) worried the secret police and Portuguese military the most. Listening to them could get you arrested. That is what happened to Chingualulo and da Silva.

Many listeners remember hiding out to listen - tucking themselves in small quiet places (under beds or desks) or in empty, open-air ones (soccer fields or rural backyards) - and passing along the information to other supporters of independence and nationalist activists. Some radio listeners recall the thrill of secret listening.

In the thousands of pages of transcribed programmes and of police reports related to radio, the secret police and military archives resound with nervousness. Despite winning the ground war, the liberation movement radios, in particular, unnerved Portuguese colonial officials. They speculated that even civil servants and "Europeans" listened. They worried about what they called the "electrifying effects" on listeners of liberation movement broadcasters, whose sounds sizzled across borders. And they proposed jamming the broadcasters but settled on counter-propaganda.

Bouncing electromagnetic waves off the ionosphere in shortwave, what liberation movement broadcasters (and other international radio) gained in distance they lost in quality at the point of reception.

The records I went through included police and military transcriptions that inscribe the fading, the lost sentences, the buzz of atmospheric interference, and the trailing off of sound.

Listeners in the territory, some like Chingualulo and da Silva, amplified the broken messages. Others passed along what they heard, becoming transmitters in their own right. Similar to Algerian listeners of the Voice of Algeria that Frantz Fanon described in A Dying Colonialism, people in the Angolan territory pieced together choppy sentences, imagining guerrillas in the bush and diplomatic sessions that debated their freedom at the United Nations.

Radio became a form of participating in the struggle. As Fanon wrote:

Canny listeners understood that the liberation movements and the colonial state (in programmes on the Emissora Oficial de Angola/Official Angolan Broadcaster) broadcast propaganda, or what Fanon calls "lies".

They didn't believe everything they heard, no matter what the source. But they also understood the stakes: independence or continued oppression under Portuguese rule.

Powerful Frequencies: Radio, State Power, and the Cold War in Angola, 1931-2002 by Marissa J. Moorman is published by Ohio University Press. Order your copy over here.

Author: Marissa J. Moorman - Associate Professor of History, Indiana University

Share

Share

Tweet

Tweet

Share

Share

Flip

Flip

Email

Email

Watch latest videos

Subscribe and Follow

Get a daily dose of Broadcast Communications news through our daily email, its complimentary and keeps you fully up to date with world and business news as well.

News RELEASES

Publish news of your business, community or sports group, personnel appointments, major event and more by submitting a news release to Broadcast Communications.

More InformationBusiness

SectionWall Street diverges, but techs advance Wednesday

NEW YORK, New York - U.S. stocks diverged on Wednesday for the second day in a row. The Standard and Poor's 500 hit a new all-time...

Greenback slides amid tax bill fears, trade deal uncertainty

NEW YORK CITY, New York: The U.S. dollar continues to lose ground, weighed down by growing concerns over Washington's fiscal outlook...

Taliban seeks tourism revival despite safety, rights concerns

KABUL, Afghanistan: Afghanistan, long associated with war and instability, is quietly trying to rebrand itself as a destination for...

Nvidia execs sell $1 billion in stock as AI boom drives record prices

SANTA CLARA, California: Executives at Nvidia have quietly been cashing in on the AI frenzy. According to a report by the Financial...

Tech stocks slide, industrials surge on Wall Street

NEW YORK, New York - Global stock indices closed with divergent performances on Tuesday, as investors weighed corporate earnings, central...

Canada-US trade talks resume after Carney rescinds tech tax

TORONTO, Canada: Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney announced late on June 29 that trade negotiations with the U.S. have recommenced...

Sectors - Broadcasting

SectionSBA participates in World News Media Conference 2025 in Poland

SHARJAH, 7th May, 2025 (WAM) -- The Sharjah Broadcasting Authority (SBA) recently took part in the 76th World News Media Congress,...

France returns military base to Senegal

Paris is withdrawing its troops after the African country scrapped a decades-old defense agreement France has handed over a military...

"Landmark day for India's efforts to encourage sporting talent": New National Sports Policy 2025 approval

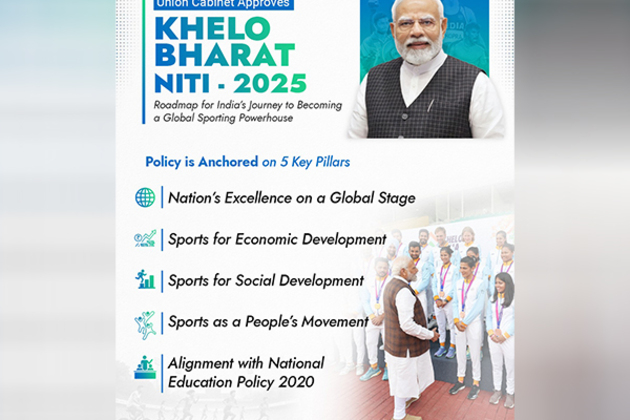

New Delhi [India], July 1 (ANI): On the occasion of the approval of the new 'Khelo Bharat Niti 2025', Prime Minister Narendra Modi...

Indian Institute of Creative Technologies begins admissions for Animation, Visual Effects, Gaming, in August

Mumbai (Maharashtra) [India], July 1 (ANI): The Indian Institute of Creative Technologies (IICT) opens admissions for its first batch...

Cabinet approves Research and Development and Innovation scheme with corpus of Rs 1 lakh crore to boost strategic, sunrise domains

New Delhi [India], July 1 (ANI): In a significant step to bolster India's research and innovation ecosystem, the Union Cabinet on Tuesday...

Georgia Risks EU Sanctions; Ukraine Hits Roadblocks In NATO, EU Bids

Welcome to Wider Europe, RFE/RL's newsletter focusing on the key issues concerning the European Union, NATO, and other institutions...